With all of the new creator resources I have here on my website, I get quite a few people asking questions and looking for one-on-one advice, unfortunately more than I can usually respond to personally. That said, if a discussion does start up and I ask you what your goals are, if you don’t know at all or want me to tell you what they ‘should’ be, you need to reevaluate.

I can’t tell you what to strive for. Your goals shouldn’t be my goals.

What I can suggest is that you build goals around things you know you can do that can’t be stopped by the decisions of other people. Here’s what I mean:

🔸Finding collaborators

🔸Making a comic, start to finish

🔸Working with a publisher

Those are actionable/attainable goals.

🔸Making a living working for Marvel/DC

🔸Topping sales charts

🔸Winning an Eisner Award

Those goals include a minefield of factors outside your control, with a high chance of failure.

Looking toward successful people in the industry is natural and understandable, but there is also a ridiculous amount of Survivor Bias built in to anything we suggest. Even if I tell you what worked for me and my career, dozens of similar people who worked just as hard didn’t get to the same spot for reasons out of their control.

Setting goals is good. Making things and finishing them is key to improving yourself and growing. Putting out creative work will always lead to new experience and possibilities, just try not to hyper-focus on specific outcomes that are outside your control.

When I went to college for Classical Animation, my goal was to be a Disney animator living in Florida or California, working on a feature animated film. Midway through school, Disney stopped making hand drawn animation. Factors outside my control had completely upended my goal and that was that.

But look at the number of “fail-states” I’d inadvertently built into my goal:

🔸Working in the U.S.

🔸For Disney

🔸on a 2D animated feature

If I was good enough, and Disney was hiring, and I qualified for a green card, and I convinced every person on that path to make the right choice my dream might have been achieved. Any part of that chain breaks and the whole thing falls apart. Disney stopped making the kinds of films I trained to work on, so I didn’t even get the chance to apply in the first place. It was a frustrating but valuable lesson.

Learning early on that the dream I had in mind wasn’t possible taught me to dig deeper to understand the heart of those goals and achievements I was striving for.

Why did I want to work at Disney on feature 2D animation?

What were the core aspects of that dream I aspired to?

🔸I wanted to create things

🔸I wanted to tell stories

🔸I wanted to be part of a group building things together

🔸I wanted to be in an environment that felt exciting, collaborative, and creative

All those could be achieved and were under my control.

The other important part of these broader goals is that they were (and still are) things that could continue to grow and continue to be a priority for me instead of being checkbox one-time ‘achievements’.

(Looking at the original goal, even if I ran the Gauntlet and made it to Disney Feature Animation and worked on a film, what then?)

Working in comics and teaching wasn’t part of my original plan, and I stumbled into both careers, and yet they both check all my boxes:

✓ Storytelling

✓ Collaboration

✓ Constantly creating

✓ Exciting and inspiring

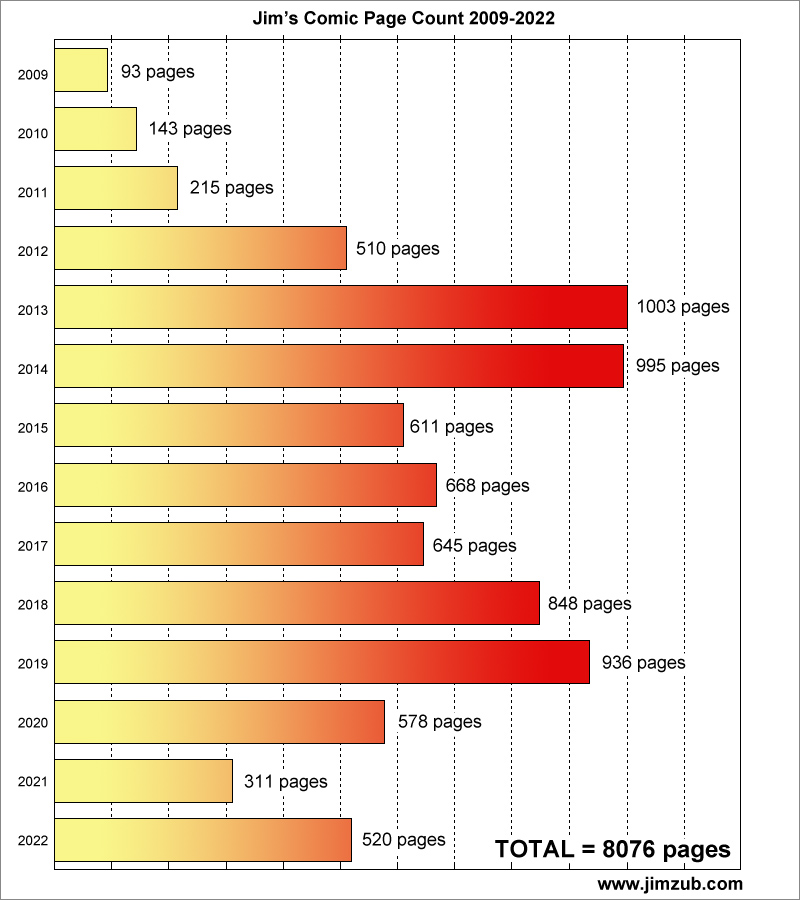

These broader goals are also not limited to doing something once – a hyper-specific credit, company, or project. I can keep doing them, keep learning, and keep growing. Some years will be less productive or less successful, but they’re always “active” goals worth pursuing, regardless of the industry or my success at any one point in time.

I can also look at future project possibilities and measure them against my ideal list to help me decide if I want to go in one direction or another.

In a video I put together a few years ago I talk about the rambling path of my comic career and you can see how varied and unexpected it is:

Thankfully, in each case, my revised list of creative goals still applies, helping keep me inspired and moving forward, project by project, and year by year.

If you found this post helpful, feel free to let me know here (or on BlueSky), share the post with your friends and consider buying some of my comics or donating to my Patreon to show your support for me writing this tutorial post instead of doing paying work. 😛

Zub on Amazon

Zub on Amazon Zub on Instagram

Zub on Instagram